The 18-Year Land Cycle: Can We Forecast the Next Market Crash? Pt. II

Part II: When Strategic Competition Trumps Housing Wealth

The Great Interruption: What Actually Broke the Cycle (1929-1973)

In normal times, the land cycle runs as a feedback loop. Rising land values lead to more bank lending, which enables more construction, which creates an economic boom, which drives overvaluation, which eventually triggers a credit crisis, which leads to collapse, which clears the decks for the next cycle. The mechanism depends on one thing working. The ability to capitalize expected future rents into a present price through the extension of private credit.

By 1929, this loop had reached a kind of global crescendo. Land values in the U.S. and U.K. had been inflated to completely unsustainable levels, all fueled by speculative credit. Then the Depression hit and completely shattered the machinery.

Almost 9,000 banks failed in the U.S. between 1930 and 1933, erasing most of the monetary base that had been fueling land speculation. Foreclosure rates surged to unprecedented levels nationwide. Land stopped being a speculative asset and became a liability. Deflation gripped the economy from 1929 through 1933, with prices falling 27%. Households and firms spent the next decade and a half digging out from under the debt they’d accumulated in the 1920s. When credit evaporates and rent expectations collapse, you can’t turn location value into a tradeable asset price anymore. The engine just stops.

Then World War II turned every major economy into a command system. Rent controls were imposed across the U.S., U.K. and Commonwealth countries. Banks could only lend under state direction. Credit was rationed according to war priorities. Civilian construction was essentially banned. Any steel, concrete, or labor was going to the war effort. Land transfers were severely restricted or controlled administratively. The land cycle cannot operate without free-market rents and private credit creation. The war replaced both with bureaucratic allocation, making land speculation institutionally impossible.

After WWII, governments were determined to prevent a repeat of the 1930s. The Depression had taught them that unstable international capital flows could force countries into deflationary spirals. When money fled across borders, central banks had to raise interest rates to defend their currencies, deepening the crisis. The gold standard had transmitted America’s collapse worldwide through forced deflation. So policymakers built the Bretton Woods system around capital controls. They distinguished between “productive” capital for trade and investment versus “hot money” speculation. The goal was simple. Trap capital inside national borders so governments could pursue full employment and national industrial policy without worrying about destabilizing flows. Economists later termed these domestic policies ‘financial repression.’ The Fed and other central banks kept interest rates fixed at low levels, often below inflation. Capital controls restricted money from flowing across borders. Banks operated under credit quotas and rationing. They couldn’t just lend to whoever they wanted. Rent controls and planning acts limited how much landlords could charge. Public housing programs absorbed a big chunk of demand.

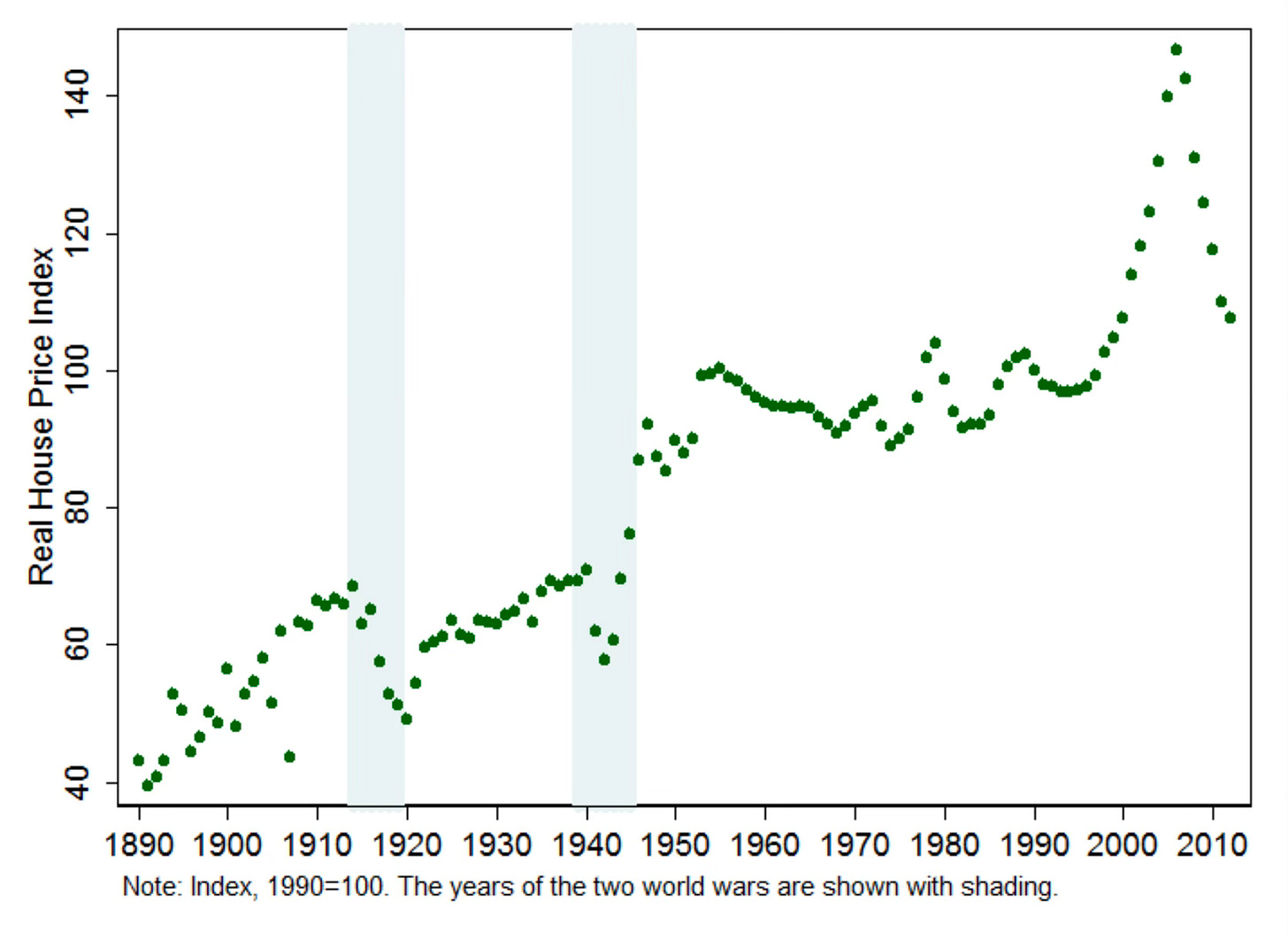

The below graph from Knoll, Schularick & Steger’s landmark study shows what happened to U.S. real home prices over this period:

US Real Home Prices 1870-2012

Source: American Economic Review, “No Prices Like Home: Global House Prices 1870-2012

The Depression devastated housing. Nominal prices crashed 25-35% nationally, with Manhattan dropping 67%. But in real terms, inflation-adjusted values fell only about 7% from 1929 to 1933. Why? The economy experienced 30% deflation. Nominal prices crashed, but purchasing power collapsed faster. By 1940, real housing prices had actually recovered above 1929 levels.

But World War II showed something different. Government could crash real housing prices instantly when it decided to redirect resources to strategic production. Government severely restricted civilian construction, rationed materials to war production, imposed rent controls nationally, and directed all steel, concrete, and labor to strategic priorities. Meanwhile, wartime spending created inflation. Rent controls kept nominal rents flat while inflation eroded their real value. Real housing prices fell off a cliff from 1940 to 1945.

Then came demobilization. Sixteen million servicemembers returned home between 1945 and 1947 to a housing stock that hadn’t expanded in fifteen years. The GI Bill offered zero-down mortgages at below-market rates. Household formation exploded. Real housing prices spiked from 1945 to 1950 as families competed for limited supply, the only sustained increase between 1930 and 1970.

But then comes the interesting part. From 1950 through 1970, twenty years, real housing prices gradually declined. This wasn’t market failure. This was financial repression working exactly as designed.

Interest rates stayed below inflation. Capital controls restricted credit. Government directed investment toward Cold War priorities from defense spending to highway systems and space programs. Rent controls persisted in major cities. Public housing absorbed demand. The Federal Reserve kept mortgage credit rationed.

The postwar system deliberately capped rents and contained prices, suppressing the cycle’s amplitude by design. For roughly 40 years, two full theoretical cycles, government controlled the key variables that enable land speculation.

Homeowners watched their primary asset depreciate in real terms for twenty years. They accepted it. Housing was shelter, not an investment vehicle. Nobody expected to get rich from rising home values. Americans didn’t just tolerate this. They demanded it. Making housing affordable was popular policy. Limiting speculation had broad support. Progressive reformers, New Deal Democrats, postwar leaders all ran on platforms of affordable housing and strategic capital allocation.

This addresses a crucial question about political feasibility.

Americans in the 1930s-1970s accepted housing as utility rather than investment because the political economy created conditions where that choice became not just viable but necessary. The United States faced existential competition with alternative economic systems that claimed to solve capitalism’s failures. A broad social consensus emerged that speculation was harmful and destabilizing. Political coalitions formed across the spectrum that prioritized housing affordability over asset appreciation. And critically, government maintained the legitimacy to direct capital allocation toward strategic national objectives rather than private wealth accumulation.

By the early 1970s, policy makers’ explicit attempts to moderate the economic cycle started to crack. Inflation surged, making Bretton Woods fixed interest rate policies unsustainable. Financial liberalization started in 1971 with Savings & Loan deregulation in the U.S. and “Competition and Credit Control” reforms in the U.K. Rent controls gradually eased. Mortgage finance expanded. Land became banks’ favored form of collateral again.

Once governments loosened the controls that had been suppressing land speculation and private credit creation, the boom-bust dynamics reemerged. Whether they returned on a precise 18-year schedule is hard to argue with a straight face. The pattern isn’t perfect, but it’s arguable the cycle resumed with relatively clean runs from 1973-1990 and 1990-2008.

China: When Government Chooses Strategic Industries Over Housing Wealth

If the ‘financial repression’ era proved governments can suppress the land cycle through direct control, China just demonstrated they can do it too. Deliberately, strategically and at scale that makes postwar America look timid.

China’s real estate bubble inflated from 2000 to 2021 (21 years, not 18). At its peak, property comprised 70% of household wealth. Developers were levered 50:1 or more.

The interesting part isn’t the bubble. It’s the controlled deflation.

Starting in 2017, Xi Jinping stated “houses are for living in, not for speculation.” This converted into a state mandate in 2020 when the “Three Red Lines” policy imposed hard leverage limits on developers. If you violated thresholds, you couldn’t borrow for new projects. The policy worked as intended. Evergrande defaulted in 2021 with $300B+ in liabilities. Country Garden followed. Dozens of smaller developers collapsed. Property values have been deflating since 2021.

The Chinese government absorbed losses through state-owned banks rather than letting the financial system collapse. No acute banking panic, just slow grinding deflation managed from the top. This wasn’t crisis management, it was deliberate policy.

As Louis Vincent-Gave argues in his analysis of US-China competition, the real estate deflation was a strategic choice. The Chinese government deliberately redirected capital away from property speculation and toward moving up the industrial value chain via semiconductors, electric vehicles, advanced manufacturing and artificial intelligence. The real estate bust was the cost of that strategic decision.

For two decades, Chinese households poured their savings into real estate because it was the only reliable wealth store available. Then the government decided that capital needed to go to strategic industries instead. So they engineered a deflation that’s actively destroying household wealth while channeling investment toward industrial competitiveness.

This is financial repression at a scale the West hasn’t attempted since the 1940s-60s. Deliberately suppressing one sector to fund another. Directing capital allocation through administrative fiat rather than market signals. Maintaining political stability while household wealth craters.

Vincent-Gave poses a crucial question. Would American voters today accept watching their home equity evaporate for the sake of national competitiveness?

His answer? No. American voters want industrial policy AND rising home values AND strong consumption. They won’t tolerate getting crushed financially while the government redirects capital to semiconductors and strategic industries. So the US would have to fund industrial policy through currency debasement instead—print money to pay for it all without forcing the pain onto households through deflation.

But that assumption deserves scrutiny. Because we have a precedent for American voters accepting exactly this kind of wealth destruction in housing. Real home prices were essentially flat or down for most of 1930’s/1940’s and declined for twenty straight years from 1950 to 1970. Homeowners watched their primary asset depreciate and accepted it. What made that politically viable then? And could similar conditions emerge now?

The Great Interruption 2.0

In the 1930s, Western capitalism faced existential competition. Soviet communism claimed to have found a better way. Italian fascism offered a different model. German national socialism presented yet another alternative. Each promised to solve capitalism’s apparent failures: unemployment, inequality, instability, boom-bust cycles.

We’re back in that kind of moment.

Today, Chinese state capitalism is demonstrating that centralized control and strategic capital allocation can deliver sustained growth, infrastructure development, and technological advancement.

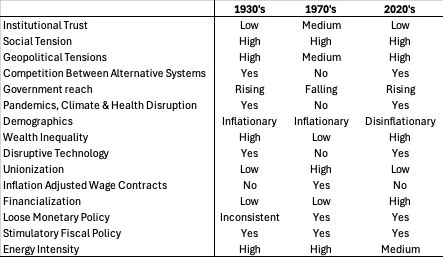

Viktor Shvets compiled this comparison in his recent book Twilight Before the Storm. When you score the 2020s against historical periods across institutional trust, geopolitical tensions, competition between alternative systems, wealth inequality, and government reach, we don’t look like the 1970s or 1990s or 2000s. We look like the 1930s.

Political polarization in the U.S. and Europe reflects genuine uncertainty about whether the post-1980 neoliberal consensus actually delivers for most people: rising populism on both left and right, declining faith in institutions, increasing social tensions, and growing wealth inequality. All of this echoes the 1930s directly.

The 1930s eventually resolved through depression and war, producing the Bretton Woods system and welfare-state capitalism that lasted until the 1970s. We don’t know yet what comes out of the 2020s. But the systemic competition creates conditions where governments might make choices that would have been politically impossible a decade ago.

Like intervening in markets and the economy for strategic objectives.

The political coalition already exists. A populist right worried about American decline and unaffordable housing plus a progressive left focused on inequality and financialization. Both see asset owners getting richer while everyone else suffers. What’s missing isn’t the political will. It’s a crisis severe enough to force the decision.

To address the series of rolling crises during 1930s and 1940’s, government didn’t just tweak policy around the edges. It took control. Not just of interest rates, but of production, employment, capital allocation, wages and prices.

And we have been slowly but steadily rebuilding that infrastructure of government control for almost 20 years.

Government as Credit Allocator

Post-financial crisis, the Fed’s mandate expanded to what are now recognized as “inherently political activities such as credit allocation and the selection of economic winners and losers.” Emergency programs blurred the line between monetary and fiscal power. The Fed wasn’t just managing money supply. It was backstopping specific markets and more controversially supporting specific institutions.

The 2010 Dodd-Frank Act codified a critical change. Fed emergency lending facilities would now require Treasury authorization. As observers noted, “the wall between independent central banking and government spending effectively crumbled.” The Fed can’t act unilaterally in crisis anymore. Every emergency intervention draws the executive branch deeper into monetary management. What was supposed to be separation between independent central banking and government became coordination by necessity.

The March 2020 market invention necessitated by the COVID pandemic took this to another level entirely. The Fed-Treasury coordination didn’t just support banks. It backstopped corporate debt, municipal bonds, even junk-rated securities. The Fed was buying assets it had never touched before, but only with Treasury backing and approval. Emergency became precedent. The lines that were supposed to separate monetary and fiscal policy disappeared in practice.

Fed-Treasury coordination became standard operating procedure under the Biden administration with the Treasury effectively acting as a shadow central bank. While the Fed was hiking interest rates aggressively through 2022-2023, the Treasury was actively loosening financial conditions through debt maturity management. They issued more short-term bills that functioned almost like cash while buying back long-term debt, lowering yields on longer maturities. This wasn’t subtle. Economists Stephen Miran and Nouriel Roubini calculated that Treasury policy had the same effect as a 100-basis-point reduction in the Fed’s policy rate, completely offsetting the 2023 interest rate hikes. This explains something that confused most economists. Why the fastest rate hike cycle in recent decades didn’t trigger a recession? Because as Miran and Roubini noted, “the Fed-Treasury balance sheet matters for markets and the economy, not either in isolation.” The Fed was tightening. Treasury was loosening. The net effect was neutral.

Stephen Miran joined the Federal Reserve Board in 2025. His public work before joining makes explicit what had been operating quietly for years. Monetary policy is now politics conducted by other means. His position isn’t to restore Fed independence. That ship has sailed. His position is to make Fed-Treasury coordination formal and accountable. As he writes, “If the Fed is already political, the answer is not to restore a lost neutrality. It is to make that power accountable. The only way out is through.” Success, he argues, “will likely depend on renewed cooperation between the Fed and the Treasury” with “public support from the President.” Bessent is continuing the activist Treasury approach (despite having criticized it before joining the administration) by still issuing heavy short-term debt to suppress long rates and conducting outright buybacks of long-term bonds if needed to cap yields. As one assessment puts it “The neoliberal order that kept markets and politics apart is gone.” This isn’t speculation about future policy. This is the stated framework of a sitting Fed Governor.

If Miran represents the intellectual architecture, Bill Pulte, the current director of the Federal Housing Finance Agency and the chairman of Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac represents operational deployment.

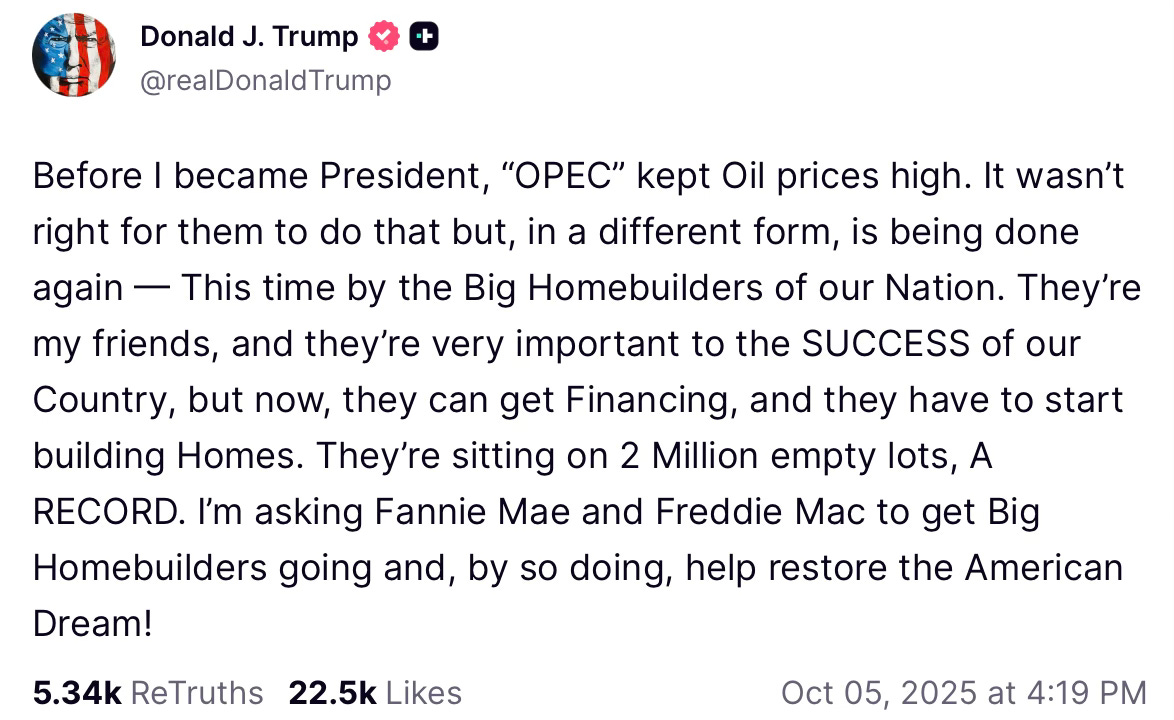

In October 2025 President Trump began publicly pressuring large homebuilders to “build more homes” and bring prices down.

Pulte amplified the message, accusing big builders of acting as a coordinated oligopoly that controls roughly 55% of new-home supply. Whether that characterization is fair matters less than the signal. The government is willing to use political pressure and regulatory leverage to force private companies to increase production.

In a blitzkrieg of mortgage-related announcements in November 2025, the Trump administration proposed 50-year mortgages (extending payment periods), portable mortgages (loans that transfer when you move), and assumable mortgages (buyers take over sellers’ existing rates), explicitly comparing the policies to FDR’s introduction of the 30-year mortgage in the 1930s. Each tool serves the same function. Use government-controlled credit to suppress monthly housing costs.

The more significant development is how far into the capital stack Fannie and Freddie are being directed to reach. Pulte has hinted in interviews that the GSEs could take equity stakes in private-sector housing companies or development vehicle. This is a significant shift from pure mortgage credit risk into direct capital participation. They could also provide quasi-construction financing structured as permanent loan commitments. Essentially funding development by guaranteeing the permanent financing upfront rather than waiting until construction completes. Policy discussions center on GSE support for build-to-rent, manufactured housing communities and direct development financing. The objective is clear. Use government-controlled mortgage finance to materially increase housing supply. None of these moves require new legislation. They’re all achievable through administrative action and executive pressure. The infrastructure for government control already exists. What’s changing is the willingness to use it explicitly.

The housing deployment sits within a broader framework. The CHIPS Act, Inflation Reduction Act, and Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act together represent about $1.8 trillion in direct government capital allocation that picks winners in semiconductors, clean energy and infrastructure. Fed-Treasury explicit coordination and now established precedence of deeply intervening in capital markets. The government is taking direct equity stakes in strategic rare earth miners, semiconductor manufacturers, contemplating investments in defense contractors. Pulte is directing GSE capital toward housing supply, potentially taking equity stakes in development vehicles. Miran is making explicit what’s been implicit since 2008. Monetary policy has become a tool for industrial and social policy, not just price stability.

This isn’t industrial policy in the gentle sense. This is government becoming a direct participant in capital allocation decisions. Not crisis management but a deliberate policy with a coherent framework behind it.

Which brings us to the question: what happens next?

Three Scenarios for What Happens Next

The question isn’t whether we’re in late stages of the current cycle. We clearly are. The question is what happens from here. I see three possible scenarios:

Scenario 1: The Cycle Turns (2026-2027)

This is what the cycle theorists expect. Housing prices decline materially. Regional bank failures start emerging. Credit markets freeze up. Recession hits. The classic late-cycle sequence.

What would actually confirm this? National single-family home prices down 15% or more by end of 2027. Multiple regional bank failures driven specifically by real estate-related credit losses. CMBS market genuinely seizes up. Not just elevated delinquencies but an actual market freeze. NBER declares a recession with real estate and finance as the primary cause.

If this plays out, the investment implications are straightforward. Cash is king. You wait for the distress. You buy the bottom sometime in 2027-2028. This becomes the classic “be greedy when others are fearful” opportunity that value investors dream about.

Scenario 2: COVID Reset the Clock (2020-2038)

This was cycle proponent Fred Foldvary’s view before he died in 2021. He concluded that COVID was a “reset event” similar to the Great Depression. Forbearance kept failing borrowers afloat. Stimulus checks kept the economy humming. The whole system went into this weird suspended animation. All of that fundamentally broke the cycle’s normal progression.

In his view, the cycle essentially starts over from 2020, which means the next peak wouldn’t arrive until the late 2030s.

What would confirm this: Housing markets stabilize through 2027-2028 without any major crashes. Banks muddle through with manageable losses but no systemic failures. No major crisis materializes, just continued stagnation and slow recovery. Then another boom phase begins to develop in the early 2030s.

If this scenario is right, the investment implications are completely different. We’re actually in early-to-mid cycle right now, not late cycle. Current caution would be premature. You could deploy capital on 5-7 year hold periods expecting appreciation through the 2030s. Being defensive right now would mean missing the entire next expansion phase.

Scenario 3: Financial Repression (My Base Case)

This is what I actually think is happening. It’s also the most complex scenario to navigate.

The mechanism is real. Credit-fueled land speculation creates boom-bust dynamics. But we’re entering a new regime where governments and central banks have both the tools and the political will to intervene in ways that fundamentally alter the cycle’s trajectory.

Financial repression isn’t new. It’s what governments do when debt becomes unmanageable. Economists Carmen Reinhart and Belen Sbrancia documented how this worked from 1945-1980. Governments held interest rates below inflation, forcing pension funds, banks and insurance companies to buy government debt regardless of return. This quietly transferred wealth from savers to debtors at 3-5% of GDP annually. Financial historian Russell Napier argues we’ve entered a new 15-20 year cycle of financial repression. Similarly to the previous period, governments will direct credit toward politically favored uses (strategic industries, infrastructure, affordable housing) while starving “unproductive sectors”.

This is occurring in real time.

Treasury-Fed coordination to control rates has become explicit policy. The Fed now backstops corporate debt, municipal bonds and junk-rated securities. The government takes equity positions in strategic industries including rare earth miners, semiconductor manufacturers, even defense companies. It drives GSEs into unprecedented territory, construction lending, assumable mortgages, and developer equity stakes. All this isn’t a proposal, it’s the stated plan.

This is 21st century financial repression, negative real rates combined with explicit credit rationing and government capital allocation. It is well under way.

How to Position

The core insight is simple. Credit is being rationed and directed. Government will decides who gets it. Conventional market-rate multifamily faces harder terms and tighter credit access in an environment where government is actively rationing credit away from assets it deems unproductive. Fannie and Freddie over the years have steadily raised affordability incentives on multifamily loans for below-market rents, affordable housing set-asides and mission-driven lending targets. Their annual market share of total multifamily lending runs between 40-50%. This gives them an outsized ability to influence housing markets. As financial repression intensifies, expect these incentives to look more like requirements.

So what will work? Government in this era is intent on backstopping owner-occupied single-family homes, workforce and capital “A” Affordable (subsidized) multifamily housing. This is unlikely to change no matter what party controls Congress or the Presidency. Focusing on geographies and markets tied to strategic industries including advanced manufacturing, tech, semiconductors and defense will add alpha. Anything that delivers government affordability objectives will see credit flow freely.

What won’t work? Napier explicitly calls out commercial real estate as “unproductive,” and in a credit-rationed environment, that label determines who gets capital. Market-rate Class-A/luxury residential (outside of the high-end employment markets) will struggle to achieve rent growth above inflation and will receive lesser financing terms. The short duration buy-renovate-exit playbook that was so lucrative this cycle will carry more negative optics and political risk. Value-add will have to add real value (think adding additional units or bringing uninhabitable units online). Anything seen as investor speculation rather than housing provision will face headwinds.

This is a fork in the road for housing investors. Many of the most successful strategies of the last cycle won’t work going forward. Go back to as recently as the 1990s most of investment housing’s total returns came primarily from cash flow rather than appreciation. That’s the world we’re returning to. Average hold periods will need to extend substantially. There’s a reason every deal used to be underwritten as a 10-year DCF. Maybe we should think even longer term. Partnership structures will need to be updated to reflect this new reality. You will once again need to be a strong operator (or invest with one) once more. This last cycle saw many inexperienced housing investors ride massive rent growth and cap rate compression to great success. That is unlikely to repeat.

Ultimately many of these dynamics will bring more balance to housing markets. Housing is after all, where workers in the economy live. In the long run, housing values and rents cannot exceed economic growth without serious negative externalities. Real estate has always been a “get rich slow” strategy that got out of whack this last cycle.

The data now shows we’re returning to that reality. The investors who understand this shift early will compound wealth. Those waiting for 2019 to return will be left holding expensive, low-yielding assets in a world that’s moved on.

Next in this series: What the current housing data is actually telling us about where we are right now. Multifamily fundamentals. Single-family trends. Land prices. Credit conditions. Where the actual stress points are as we speak.

“♡ Like” — it won’t stop the next cycle, but it might help you see it coming.

Primary Sources Cited:

Knoll, K., Schularick, M. & Steger, T. (2017). “No Price Like Home: Global House Prices, 1870-2012.” American Economic Review, 107(2), 331-353. [Graph data shown in text]

Shvets, V. (2024). Twilight Before the Storm. [Comparative framework graph shown in text]

Reinhart, C. & Sbrancia, M.B. (2011). “The Liquidation of Government Debt.” NBER Working Paper 16893. [Linked in text]

Napier, R. (2021). “We Are Entering a Time of Financial Repression.” Interview with Mark Dittli, The Market NZZ, July 14, 2021. [Linked in text]

Miran, S. & Roubini, N. (2024). “Activist Treasury Issuance and the Yield Curve.” Hudson Bay Capital Research. [Linked in text]

Miran, S. (2024). “A User’s Guide to Restructuring the Global Economy.” Hudson Bay Capital Research. [Linked in text]

“Stephen Miran’s Post-Neoliberal Economics.” (2025). Compact Magazine. [Linked in text]

Vincent-Gave, L. (2025). “The Wrong Question To Ask.” Gavekal Research. [Linked in text]

Foldvary, F. (2021). Various writings on real estate cycles and COVID as reset event. [Referenced in text]

Government Policy Documents & Statements:

Xi Jinping (2017). “Houses are for living in, not for speculation” policy directive. Chinese government statement.

China’s “Three Red Lines” Policy (2020). Developer leverage restrictions. Ministry of Housing and Urban-Rural Development.

CHIPS and Science Act (2022). Public Law 117-167.

Inflation Reduction Act (2022). Public Law 117-169.

Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act (2021). Public Law 117-58.

Dodd-Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act (2010). Public Law 111-203.

Trump, D. (October 2025). Social media statements on homebuilder production. [Screenshot shown in text]

Pulte, B. (2025). Various statements and policy announcements as FHFA Director. Federal Housing Finance Agency.

Additional Background Sources:

These sources informed the analysis but are not directly cited in the text:

Cochrane, J. & Pawson, H. (2020). Australian residential price periodicity research.

Vincent-Gave, L. (2024). “Avoiding the Fate of the Ming Dynasty.” Gavekal Research.

McKinnon, R. (1973). Money and Capital in Economic Development. Brookings Institution.

Shaw, E. (1973). Financial Deepening in Economic Development. Oxford University Press.

Rogoff, K. & Yang, Y. (2021). “Peak China Housing.” NBER Working Paper 27697.

Chen, K. & Wen, Y. (2017). “The Great Housing Boom of China.” American Economic Journal: Macroeconomics, 9(2), 73-114.

Anderson, J. (2024). “China’s Property Sector: From Ponzi to Policy.” Emerging Advisors Group.

Jackson, K. (1985). Crabgrass Frontier: The Suburbanization of the United States. Oxford University Press.

Fetter, D. (2013). “How Do Mortgage Subsidies Affect Home Ownership?” American Economic Journal: Economic Policy, 5(2), 111-134.

Fishback, P. et al. (2011). “The Influence of the Home Owners’ Loan Corporation on Housing Markets During the 1930s.” Review of Financial Studies, 24(6), 1782-1813.

Friedman, M. & Schwartz, A. (1963). A Monetary History of the United States, 1867-1960. Princeton University Press.

Rockoff, H. (1984). Drastic Measures: A History of Wage and Price Controls in the United States. Cambridge University Press.

Mills, G. & Rockoff, H. (1987). “Compliance with Price Controls in the United States and the United Kingdom During World War II.” Journal of Economic History, 47(1), 197-213.

Krippner, G. (2011). Capitalizing on Crisis: The Political Origins of the Rise of Finance. Harvard University Press.

Helleiner, E. (1994). States and the Reemergence of Global Finance. Cornell University Press.

Napier, R. (2022). “The world will experience a capex boom.” Interview with The Market NZZ, October 14, 2022.