Subsidizing the Bid

How Fannie and Freddie Inflate Housing Prices

If you want to make something more affordable in America, there’s a standard playbook. Make the financing cheaper.

It works great for cars and couches. It works less great for anything that can’t be produced quickly.

That’s the trap hidden inside the “affordability” mission of Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac. The story is noble. The mechanism is mechanical. And the outcomes on price, on leverage and on who’s actually on the hook are not what the mission statement implies.

“They perform an important role…to provide liquidity, stability and affordability to the mortgage market.”

— Federal Housing Finance Agency (FHFA), "About Fannie Mae & Freddie Mac"

Liquidity. Stability. Affordability. Three words that sound like the same thing until you put them in a market where supply can’t move quickly.

Because “affordability,” in practice, doesn’t get delivered as a cheaper house. It gets delivered as a cheaper monthly payment. That subtle distinction is where the paradox lives.

The $200 Billion Question

This week, President Trump announced he’s directing his administration to purchase $200 billion in mortgage-backed securities to “lower rates” and help housing affordability.

There’s a lot in that post—Crime, Inflation, Afghanistan, Open Borders—but let’s focus on the housing piece. $200B in MBS purchases to “lower rates” and help affordability.

If you believe GSE subsidies create affordability, this should work. Lower rates → lower payments → more people can afford homes.

If you understand how subsidies work in supply-constrained markets, you know exactly what happens next: Lower rates → higher bids → same payment, higher price → sellers capture the benefit.

We’re about to run this experiment again. In real time. At $200 billion scale.

Let’s talk about why the result is already determined.

The Payment Society

Picture a couple at an open house. They’re not running discounted cash flow models. They’re converting their paycheck into the largest possible mortgage payment that won’t crater their lifestyle.

They aren’t thinking about asset prices. They’re thinking about monthly cashflow. What number keeps the checking account functional.

Their lender knows this too. So the pre-approval doesn’t start with the home price. It starts with the payment. Rate goes into the machine. Maximum loan comes out.

Lower the rate and the machine produces a bigger number.

The Payment Machine:

At 7% rate: $3,000/month payment = ~$450,000 loan

At 6% rate: $3,000/month payment = ~$500,000 loan

At 5% rate: $3,000/month payment = ~$560,000 loan

Lower the rate a full two percentage points. Same monthly outflow. But a 25% higher purchase price. Zero improvement in affordability.

That’s not theory; it’s the central operating system of American housing. We live in a payment society. The sticker price is just whatever clears the payment market.

So when policy makes mortgage credit cheaper or more plentiful, it doesn’t simply “help the buyer.” It expands the buyer’s bid (and the size of bid pool). In a supply-constrained market, expanded bids don’t sit politely on the sidelines. They get capitalized.

A Federal Reserve paper draws the uncomfortable conclusion plainly. Mortgage subsidies “reduce effective mortgage rates and increase house prices.” And when housing supply is inelastic, which it is in most desirable markets, the subsidy “may hurt borrowers” because prices rise enough to fully offset the payment benefit.

So the policy meant to help you buy a home can make you worse off because the price increase eats the interest savings.

That’s the paradox in one sentence. The tool meant to make homes cheaper can make them more expensive. Especially where building is slow, uncertain and politically throttled.

The Free Option

The payment society has another feature. It’s a one-way bet.

When rates fall, you refinance. You lock in the lower payment and pocket the savings. When rates rise, you stay put. Your payment doesn’t move.

That’s not how most markets work. In most markets, when the price of the underlying thing changes, you eat the change. But the 30-year fixed mortgage with free refinancing is different. It’s an option. Specifically, a prepayment option embedded in the loan.

And who writes that option? Who’s on the other side of that trade?

In a purely private market, the investor in the MBS would eat the duration risk—and price it accordingly. When rates fall and borrowers refi, they’re left holding securities that prepaid early. Reinvestment risk. When rates rise, they’re stuck with low-yielding paper. Extension risk.

But the GSE guarantee changes the math. Because the Enterprises absorb the credit risk and standardize the product, MBS investors can accept lower compensation for prepayment risk. The option becomes cheap.

So the subsidy isn’t just “cheaper credit.” It’s cheaper credit plus a free option to refinance when rates fall.

Here’s how the risk actually moves. The GSEs themselves hold massive duration-sensitive portfolios and guarantee pools whose prepayment behavior whipsaws with rates. When rate volatility hits, those mismatches show up on the Agencies’ books. And when losses exceed their capital buffer? Treasury steps in.

That’s not a static subsidy. That’s a ratchet. Every rate drop lets borrowers lock in gains. Every rate rise leaves them insulated. And across millions of borrowers, the accumulated risk has to go somewhere.

It goes to taxpayers.

Homeowners shed their interest rate risk. The GSEs absorb it into their duration book. And taxpayers ultimately backstop the GSEs when that risk materializes.

Call it what it is. Homeowners get cheap insurance against interest rate volatility and taxpayers write the policy.

The Self-Fulfilling Prophecy

Now zoom out from the open house and look at the machinery.

Fannie and Freddie were designed to make mortgages behave like a standardized product. A conforming loan is not just a loan, it’s a template. A widget that can be pooled, securitized and sold.

That’s not a minor detail. Standardization is the difference between a thin market that panics and a deep market that clears.

Congress's own language about Fannie's purpose—"Provide stability in the secondary market for residential mortgages..."—tells you what the system is actually for.

Stability is a euphemism for something very specific. Keeping the funding spigot from seizing up when private capital gets cold feet.

The implicit claim is without the GSEs, the mortgage market would freeze in a crisis, rates would spike and the economy would collapse.

Maybe. But that’s also a self-fulfilling prophecy. You’ve made the system dependent, then pointed to the dependency as proof the system is necessary.

That’s not the same as proving the system was necessary to begin with.

The Urban Institute’s Housing Finance Chartbook shows how dominant that machinery has become. In Q2 2025, agency MBS accounted for 64.8% ($9.4 trillion) of total mortgage debt outstanding.

Read that again. Not 6%. Not 16%. Roughly two-thirds.

This is not a niche corner of the market where policy can experiment without consequence. This is the market.

Which raises a question nobody likes asking out loud. When you call something “affordability policy,” but it’s implemented as a demand backstop across most of the mortgage system... what exactly are you subsidizing?

The honest answer? You’re subsidizing the bid.

The Subsidy Follows Dysfunction Upward

If the bid subsidy were static, the argument would be simpler. You could debate whether the benefit is worth it.

But the system is not static. The subsidy follows prices upward.

Every year, the conforming loan limit tells you what the machine is willing to absorb. It’s a boundary line between “normal mortgage” and “jumbo,” between the subsidized channel and the more purely private one.

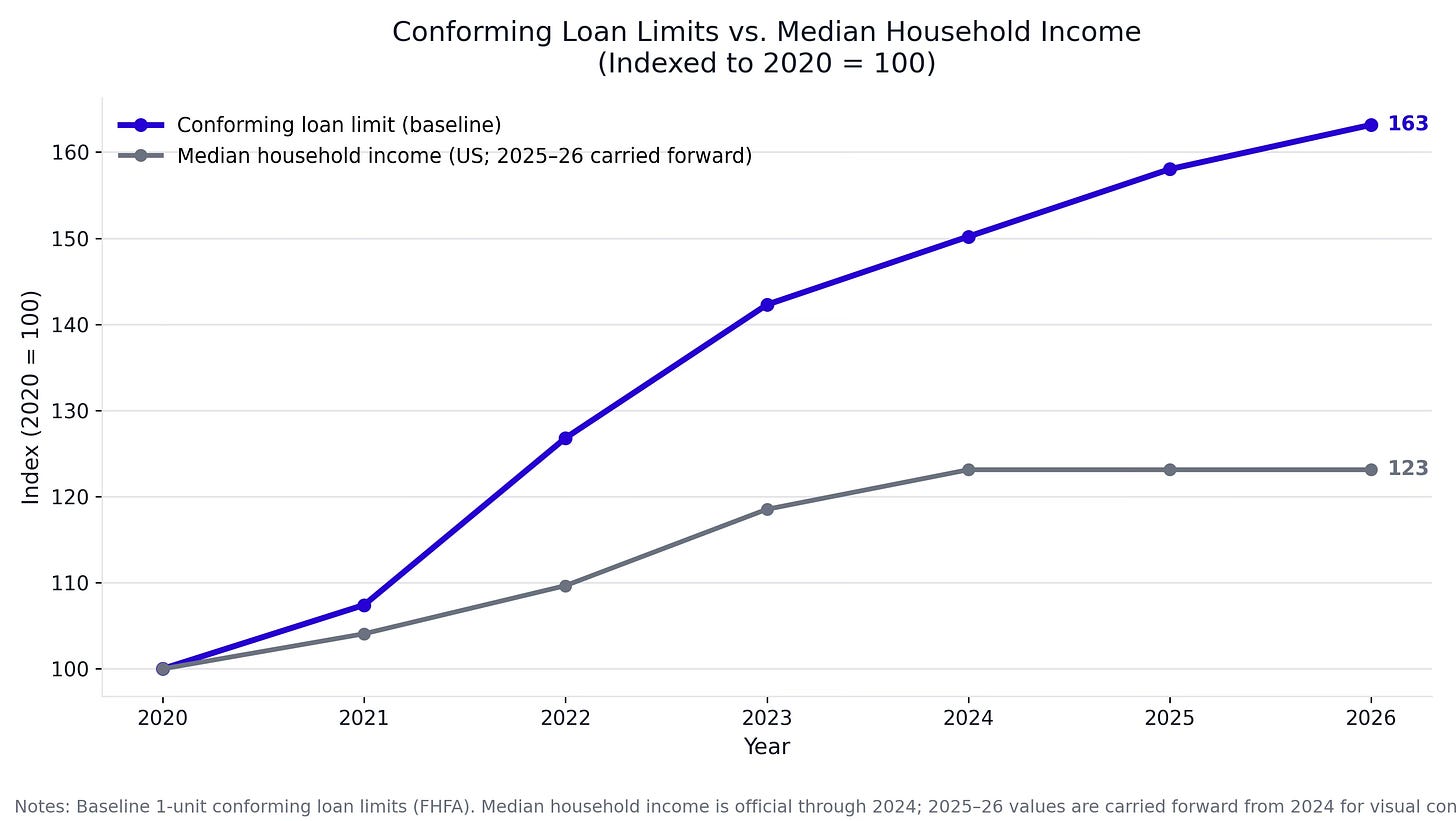

On November 25, 2025, FHFA announced the 2026 baseline conforming loan limit for one-unit properties would be $832,750. That’s a 63% increase in six years. Median household income over the same period? Up about 20%.

Source: FHFA, FRED, Housing+Markets

But the conforming loan limit isn’t one number. It’s a schedule.

In “low-cost areas” (which is most of America), the baseline is $832,750 for 2026. But in “high-cost areas”—places like San Francisco, New York, parts of Southern California—the limit can go as high as 150% of the baseline.

Which means the system delivers bigger subsidies to expensive markets.

A borrower in Boise getting a $400K mortgage gets GSE liquidity and pricing. A borrower in San Francisco getting a $1.2 million mortgage? Same benefit. Bigger absolute subsidy.

This isn’t a bug in the system. It’s a feature baked into the statute. The GSEs are supposed to serve the whole country, so the limits adjust for local prices.

But notice what this means. As coastal housing markets become more expensive, often due to supply constraints that have nothing to do with credit markets, the conforming limit rises to accommodate them. Which expands the bid support in exactly the markets where supply is most constrained.

You end up with a self-reinforcing loop:

Restrictive zoning drives up prices → FHFA raises the local conforming limit → more buyers can bid higher with subsidized credit → prices rise further → repeat.

The subsidy follows dysfunction upward.

That’s the circularity in plain sight. As prices rise, the boundary expands. As the boundary expands, more high-dollar loans fit into the standard, liquid, government-backed channel. As more fit, demand support broadens.

None of this requires a conspiracy. It requires only incentives and arithmetic.

The Proof In the Distribution

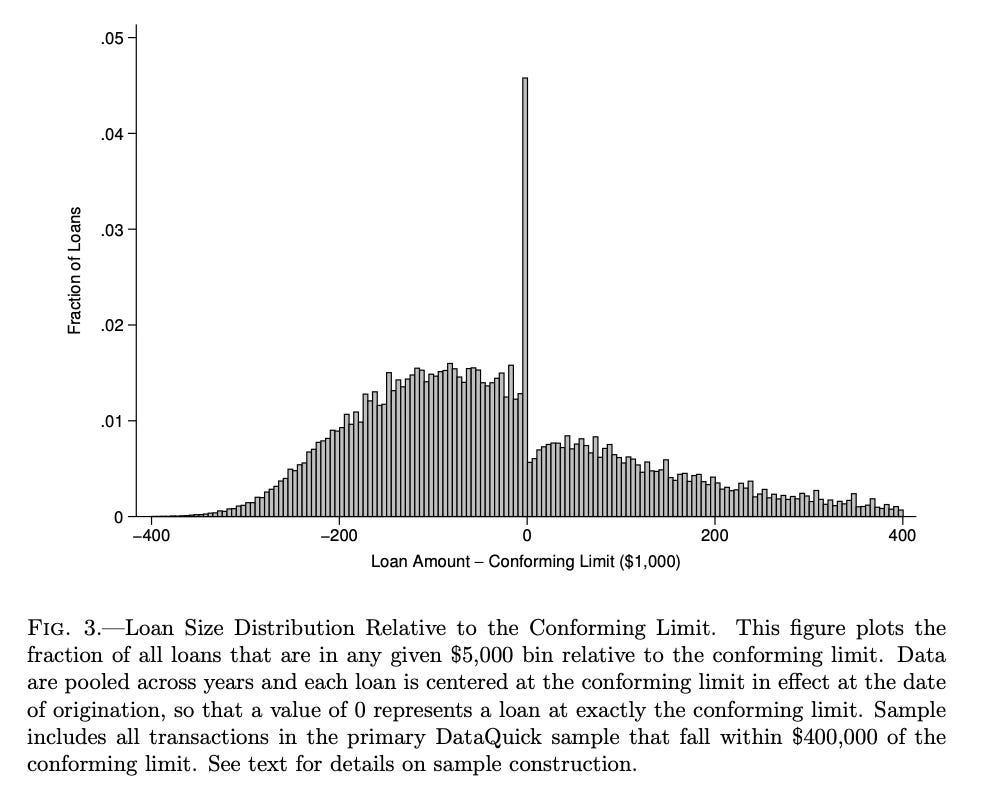

If you want to see the subsidy in the data, don’t look at the aggregate price level. Look at the distribution.

Home prices don’t spread evenly across the market. They cluster. And one of the places they cluster most reliably is just under the conforming loan limit.

This isn’t subtle. When economists at the Federal Reserve studied mortgage bunching behavior, they found exactly what you'd expect. A sharp spike in loans precisely at the conforming limit, with a visible gap just above it. Borrowers bunch at the edge of the subsidy.

Source: The Federal Reserve, De Fusco et all

Sellers know this. So do realtors. The limit becomes an attractor. Homes get priced to clear at the highest subsidized bid.

And here’s the circularity again. As prices rise, FHFA raises the limit. As the limit rises, the attractor moves up. And the market learns that the subsidy zone is elastic, it expands to meet you.

This is proof of mechanism. It shows the subsidy isn’t just theoretical, it’s literally bending the price distribution.

If you want to understand why the “affordability” gains never seem to stick, start there.

What Gets Built

Subsidizing demand doesn’t create more houses. It creates more purchasing power aimed at the same houses.

In markets where supply can surge, more purchasing power can translate into more construction. In markets where supply can’t surge, more purchasing power mostly translates into higher land values and higher prices.

A payment society will use every basis point you give it to raise the clearing price.

But there’s a second-order effect that’s easy to miss. The subsidy doesn’t just affect buyers. It affects what gets built.

Homebuilders are profit-maximizing enterprises. They build to the price point where they maximize margins. And if GSE credit expansion makes it easier for buyers to afford higher prices, builders shift their product mix upward.

Why build a $300K starter home when your land costs and permitting risks are nearly the same as a $500K home and the buyer pool for the $500K home just expanded because they can now borrow more?

The subsidy doesn’t just capitalize into existing home prices. It tilts new construction toward higher price points.

Over time, you get fewer starter homes and more move-up homes. The market “upgrades” its offerings to capture the subsidy.

This is rational. It’s also why “affordability policy” delivered through credit can make entry-level housing scarcer, not more abundant.

Who’s Really Holds the Bag

At this point, defenders of the system will object. The Enterprises don’t “hand out free money.” They charge fees. They manage risk. They set underwriting standards.

All true. But that doesn’t change the economic incidence.

If the system makes credit cheaper in a supply-constrained market, the benefit gets competed into prices. The buyer thinks they’re being helped. The seller receives the help. And the next buyer inherits a new baseline.

Which brings us to the backstop.

In 2008, the answer became explicit. Treasury’s Senior Preferred Stock Purchase Agreements committed public capital to stabilize the Agencies. As of December 2025, Treasury’s liquidation preference stands at ~$367 billion—not the $191 billion they put in, but the amount Treasury gets paid first if the entities are ever wound down.

That’s not a resolved crisis. That’s a subordinated one.

Here’s the hierarchy. The GSEs’ capital buffer absorbs losses first. When it’s exhausted, Treasury (also known as taxpayers) covers the rest.

Under conservatorship, taxpayers at least get dividends for holding that risk. Under “reform and release”? Private shareholders get the dividends. The upside gets privatized. But when the next crisis hits and losses exceed the buffer, taxpayers are still on the hook—either through an explicit backstop or through the implicit guarantee the market would inevitably price in.

Heads, investors win. Tails, taxpayers lose.

So when someone says, “we can have low mortgage rates, high prices, a massive government footprint and no public risk,” you should hear it the same way you’d hear someone pitch a perpetual motion machine.

What Everyone Gets Wrong

The housing affordability debate is dominated by three myths that keep getting repeated:

Myth #1: GSEs make housing affordable

Reality: They make borrowing affordable, which makes housing expensive. The subsidy gets competed into prices, not savings.

Myth #2: Without GSEs, the mortgage market would collapse

Reality: Canada has a 66-67% homeownership rate without Fannie and Freddie. Australia: 67%. Yes, they have different structures—Canada has CMHC, Australia has different banking dynamics—but the point stands: the 30-year fixed GSE model is not the only path to broad homeownership. The idea that American housing depends on GSEs is a hypothesis defended most vigorously by people who profit from them.

Myth #3: 30-year fixed mortgages are a public good

Reality: They’re a product whose cost is hidden, not eliminated. The GSE subsidy makes them artificially cheap by transferring duration risk to taxpayers. Other countries have mortgage markets and homeownership without this structure.

These myths persist because they serve institutional interests: politicians, the GSEs themselves, the mortgage industry that depends on them, realtors who benefit from liquidity and now—investors who want an exit.

The one group that doesn’t benefit? First-time buyers. The people the “affordability mission” is supposedly designed to help.

The Way Out

None of this is an argument for abolishing the system overnight. A housing-finance regime change would be messy—and “messy” is a euphemism for rates gap wider, credit tighter, transaction volume lower, politics louder.

It is an argument for calling the thing what it is.

The Agencies can make mortgage finance cheaper and smoother. That’s liquidity and stability.

But affordability is something else. Affordability means the ratio between shelter costs and household incomes improves in a durable way.

If you deliver “affordability” by increasing the amount buyers can borrow against fixed supply, you are not lowering the cost of shelter. You are shifting the timing and the form of the cost.

You get a short period of relief, then a longer period of higher prices.

The market doesn’t thank you for cheap credit. It capitalizes it.

And when the cycle finally bites hard enough that “stability” is threatened, you learn who was really holding the risk.

If you want a housing system where affordability improves without requiring permanent demand subsidies, you eventually end up at the same list of things that make supply easier.

Not “give developers a tax credit” easier. Physically, legally and procedurally easier. Faster entitlements. More by-right housing. Less litigation roulette. More infrastructure capacity. Less regulatory uncertainty. Fewer veto points.

It’s slow work. It doesn’t fit in a press release. It offends local power. It doesn’t goose prices.

Which is exactly why it’s the only kind of affordability policy that doesn’t eat itself.

The Bottom Line

You can subsidize the payment. You can standardize the credit. You can deepen the secondary market.

But if you don’t expand the number of homes, you’re mostly just financing the same scarcity at a higher price.

That is not affordability. Its bid support with a mission statement.

Next in this series: “Fortress Level Balance Sheet” - Why the math behind privatization doesn't add up.

Sources and Further Reading

Academic / Research (credit subsidies, incidence, “bunching”)

Federal Reserve (FEDS, 2016): Do Mortgage Subsidies Help or Hurt Borrowers?

Federal Reserve (FEDS, 2014) / AEA (2017): The Interest Rate Elasticity of Mortgage Demand: Evidence from Bunching at the Conforming Loan Limit (DeFusco et al.)

Credit supply and house prices using conforming loan limit changes (Adelino et al., 2025)

Market Structure / Share of Mortgage Debt (agency footprint)

Urban Institute Housing Finance Policy Center: Housing Finance Chartbook (Q2 2025 composition; agency MBS share)

Conforming Loan Limits (baseline + high-cost ceiling mechanics)

FHFA News Release (Nov. 25, 2025): FHFA Announces Conforming Loan Limit Values for 2026 (baseline $832,750; ceiling $1,249,125 = 150% of baseline)

FHFA FAQ (2026 CLLs): statutory high-cost framework (up to 150% of baseline; set off county median home prices)

Statute / Mission Language (what the system is “for”)

U.S. Code (12 U.S.C. §1716): “provide stability in the secondary market for residential mortgages”

Conservatorship Plumbing (backstop, “protect the taxpayer,” capital retention framing)

FHFA: Senior Preferred Stock Purchase Agreements (purpose includes “protect the taxpayer”; Third Amendment background)

FHFA Fact Sheet (2008 SPSPA): senior preferred structure + liquidation preference as taxpayer protection

Treasury Senior Preferred / Liquidation Preference (company filings)

Fannie Mae (3Q 2025 press release / filing exhibits): senior preferred stock liquidation preference (as reported in statements)

Freddie Mac (3Q 2025 earnings release / supplement / 10-Q): senior preferred stock liquidation preference (as reported in statements)