Living It Up At Hotel Conservatorship

“On a dark desert highway, cool wind in my hair...” – The Eagles

In 2008, the US government rescued two mortgage giants—Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac—to the tune of $190 billion. Seventeen years later, those companies have sent the Treasury over $300 billion in dividends. The bailout has been repaid many times over.

And yet they’re still not allowed to leave government control.

The reason is almost too absurd to believe. Every dollar Fannie and Freddie retain to rebuild their capital—the cushion they need to survive without taxpayer help—increases what they owe the Treasury. Build your wall and watch the moat get wider.

That’s not a corporate turnaround. It’s a trap.

Understanding why the trap exists—and who benefits from springing it—tells you everything about what’s broken in American housing finance.

The basics. Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac don’t make mortgages. They buy them from banks, bundle them into securities and guarantee that investors get paid even if homeowners default. This guarantee is why you can get a 30-year fixed-rate mortgage at all. Without it, banks wouldn’t take the risk.

In 2008, housing prices collapsed, defaults spiked and the guarantees came due. The government placed both companies into “conservatorship”—a legal timeout while they stabilized. The deal was simple. Repay what you owe, rebuild your capital cushion and you can leave.

Simple, except for one thing. Washington kept changing the terms.

In 2012, Treasury got nervous. The rescued companies were starting to turn profits again, and nobody wanted to watch recently bailed-out institutions pile up cash while millions of Americans were still losing their homes. Bad politics.

So Treasury implemented what’s called the “net worth sweep.” Instead of letting Fannie and Freddie retain earnings to rebuild capital, every dollar of profit got vacuumed out and sent to the government. The companies couldn’t save. The timeout became indefinite.

The sweep ended in January 2021. What replaced it was not better.

Treasury rewrote the terms to let Fannie and Freddie finally keep their profits. The headline said they could rebuild capital. The fine print said something else. For every dollar retained, their outstanding obligation to Treasury would increase by the same amount.

Read that again. The companies can now save money. But saving money makes their debt larger.

This is the trap. It’s not an accident. It’s the structure.

Which brings us to the people who desperately want the trap to end. Investors currently holding Fannie and Freddie common stock.

When the companies entered conservatorship, their shares collapsed to nearly nothing. Speculators bought in cheap, betting that someday the government would release them and the stock would soar. For seventeen years, that bet has looked foolish.

Now it might pay off. In fact, if you bought in January, it already has.

Fannie Mae common stock has run from $2 to $11—a fivefold move built entirely on anticipation of a deal that hasn’t happened yet. If a deal is struck, it will run much higher.

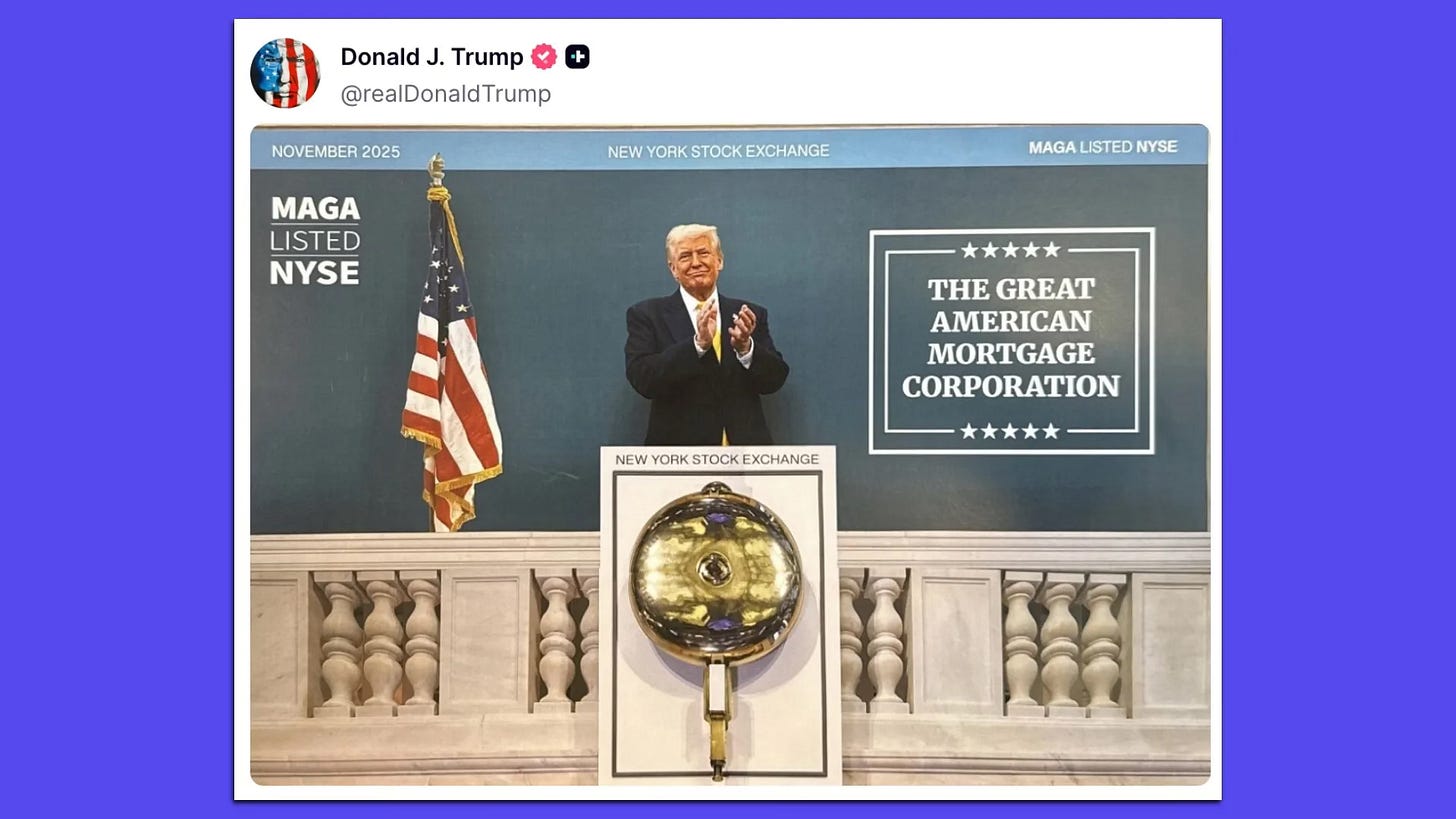

The Trump administration has made ending the conservatorship a priority. Bill Pulte, the head of the Federal Housing Finance Agency, has floated Q1 2026 as a target date for an IPO. Trump himself has been posting AI-generated images of himself ringing the NYSE bell for “The Great American Mortgage Corporation”—a rebranded and privatized Fannie and Freddie.

The recap-and-release train appears to be leaving the station.

But here’s what the enthusiasts don’t want to discuss. “Release” isn’t a date you circle on a calendar. It’s a negotiation over that $190 billion-plus IOU sitting atop the capital structure. Until Treasury’s claim is reduced, converted, or written off, the common stock is worthless—watching value accrue above its head while shareholders wait for a restructuring that may never come.

The bull case isn’t really about housing policy. It’s a workout play. Treat past dividends as “enough,” negotiate down the liquidation preference, set a capital target the market can actually finance, and exit. Thread those needles and worthless shares become a windfall.

That’s not one needle. It’s three. And the last one is where the math gets uncomfortable.

The Trilemma Nobody Wants to Admit

How much capital does it take to make Fannie and Freddie strong enough to stand alone?

Some analysts—most recently Michael Burry, the Big Short investor now making GSE recapitalization his contrarian bet—argue the path is simple. Lower the capital requirement to 2.5% (from the roughly 4% regulators currently demand), clean up the Treasury stake, and suddenly an IPO becomes feasible.

But 2.5% is an old number. And not a reassuring one.

Before the financial crisis, that was the statutory minimum. The GSEs met it. Then they blew up anyway. The system didn’t fail because there were no rules. It failed because the rules assumed national home prices don’t fall and correlations don’t go to one.

We’ve already lived through the version of history where compliance was mistaken for resilience.

The deeper problem is what happens at scale. When your exposure base is measured in trillions, a 2.5% equity layer isn’t safety. It’s a buffer for calm seas. Sufficient for the days when everything is fine. Irrelevant for the days when everything isn’t.

Mortgage stress is pro-cyclical. When unemployment spikes and housing corrects, losses don’t arrive evenly—they concentrate. That’s precisely when Washington leans hardest on the same institutions already absorbing the hit. And you don’t need catastrophic defaults for trouble to start. If markets doubt whether the equity slice can absorb what’s coming, funding costs spike and liquidity vanishes before losses even materialize.

A buffer that only works in good times isn’t a buffer. It’s a bookmark holding the page until the next bailout.

This is where the conversation has to get honest.

Most everyone involved in housing finance claims to want three things:

Enough capital for the GSEs to survive a serious crisis without taxpayer help

Low mortgage rates (meaning subsidized, whether we admit it or not)

Meaningful upside for private shareholders

The dirty secret is that you can have any two. You cannot have all three.

High capital requirements mean the guarantee gets priced honestly. Mortgage rates drift up. Credit tightens. Private shareholders can earn real returns because they’re actually bearing real risk.

Low capital requirements mean the system stays dependent on the government when stress arrives. The equity layer is window dressing. Private shareholders get upside, but taxpayers are still on the hook for the tail.

Or you can run these companies as an explicit public utility—low rates, government backstop, resilience over profits—and private shareholders become decorative. They exist, but they don’t matter.

Pick two.

The recap-and-release crowd is trying to pick three. They want cheap mortgages, private shareholder profits, and a straight-faced claim that taxpayers aren’t exposed. That’s not a policy. It’s a magic trick.

Why the Trap Never Opens

This trilemma is why conservatorship never ends.

Any real exit forces political leadership to choose what it wants the mortgage market to be.

A true private market means capital is priced, risk is borne by investors, mortgage rates can rise and access tightens when cycles turn. Most Americans would hate this.

A public utility means the backstop is explicit, the subsidy is acknowledged, and the rules prioritize resilience over pretend-privatization. Most politicians won’t admit this.

What we have instead is the third option. A hybrid that hides the tradeoffs until stress makes them visible.

The cap table might get cleaned up. An IPO might even happen. But if the “release” depends on a capital target that can’t credibly absorb a serious downturn without public support, then the release is a relabeling exercise.

The backstop stays. It just stops being called a backstop. Until the next time it’s needed.

You can check out any time you like. But you can never leave…

Hit like if you appreciate an Eagles-based title—or if you’re like The Dude and hate you can’t stand em’!