Fortress-Level Balance Sheet

Are Fannie and Freddie a fortress...or a house of cards?

Bill Ackman recently posted this, pitching one of Pershing Square’s (his hedge fund) longtime holdings.

Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac stock.

The pitch is simple: Fannie and Freddie have rebuilt their capital ratio to ~2.5%, which Ackman claims would have covered ‘nearly seven times their actual realized losses’ during the Global Financial Crisis. So they’re safe to release from conservatorship, relist on the NYSE and return to private ownership while at the same time generating $300 billion in profits for taxpayers and removing $8 trillion in liabilities from the government’s balance sheet.

It sounds compelling.

To boot, the GSEs are meaningfully stronger than they were in 2008. Underwriting standards tightened after the crisis. Documentation requirements are real, credit risk transfer deals now shift some first-loss exposure to private investors and the Agencies have accumulated roughly $173 billion in capital since Mnuchin ended the net worth sweep in 2019. These are legitimate improvements.

But here’s the problem.

If the government is going to preserve an implicit guarantee for Fannie and Freddie (and every administration official says it will) then “fortress” has to mean one thing: enough capital to survive a true housing crisis without calling on the taxpayer. Not losses tallied after the panic has passed. Capital you can actually draw on when funding markets freeze.

By that standard, the GSEs aren’t close.

We don’t need to guess what a tail event costs. We’ve lived it. In 2008, Treasury injected $191.5 billion to keep Fannie and Freddie standing on a $5 trillion book. That’s not a philosophical debate—it’s what it cost to fill the hole, in real time, when it was mission critical.

Today the book has grown to $7.7 trillion. The GSEs hold ~$173 billion in capital. And the regulator’s own stress test, using today’s improved credit profile, not 2006 underwriting, shows a combined CET1 deficit of -$115.7 billion under severely adverse conditions.

That’s not a fortress. That’s insolvency.

Ackman’s argument rests on three core claims:

(1) the math shows fortress-level capital adequacy,

(2) comparisons to private mortgage insurers validate that conclusion, and

(3) privatization would actually remove risk from taxpayers.

Each claim collapses under examination.

Stress Testing In Reverse

Here’s how Ackman arrives at “seven times actual realized losses.”

From 2008 to 2011, Treasury injected $191.5 billion to keep Fannie and Freddie solvent. That money covered credit losses, mark-to-market hits on securities portfolios, deferred tax asset writedowns and the simple fact that the GSEs couldn’t access private capital markets when they needed liquidity most. That’s what it cost to fill the hole—in real time, when it mattered.

But Ackman doesn’t compare today’s capital to the crisis-era loss number. He compares it to what he calls “actual realized losses”—and he says a 2.5% capital ratio would have covered “nearly seven times” that figure. In Pershing Square’s own deck, that “nearly seven” is 6.2x and based on an “adjusted” loss measure for 2007–2011 that uses estimated credit losses and strips out provisions and subprime/Alt-A exposure. That framing produces a much smaller loss number than what you needed to survive in the moment—before loss recoveries, accounting reversals and a healed housing market could do the work.

The distinction matters enormously. Capital doesn’t work in reverse. You can’t fill a hole retroactively. You need the buffer to exist when correlations go to one, when refinancing disappears, when the wholesale funding market seizes up—not after accountants have spent years netting out recoveries.

Treasury didn’t inject $191.5 billion because the GSEs’ long-run credit losses would eventually reach that level. It injected $191.5 billion because that’s what was required right then to cover immediate losses, restore market confidence, and provide liquidity when no private investor would. The fact that cumulative net credit losses eventually settled ~$28 billion is irrelevant to the question of how much capital you need on day one of a crisis.

Ackman’s “seven times” figure is an artifact of hindsight arithmetic. It tells you nothing about whether today’s capital would survive the next crisis without reinforcement.

What Regulators Actually Say

We don’t need to speculate about whether 2.5% is adequate. Fannie and Freddie’s regulator, the Federal Housing Finance Agency, already runs the test.

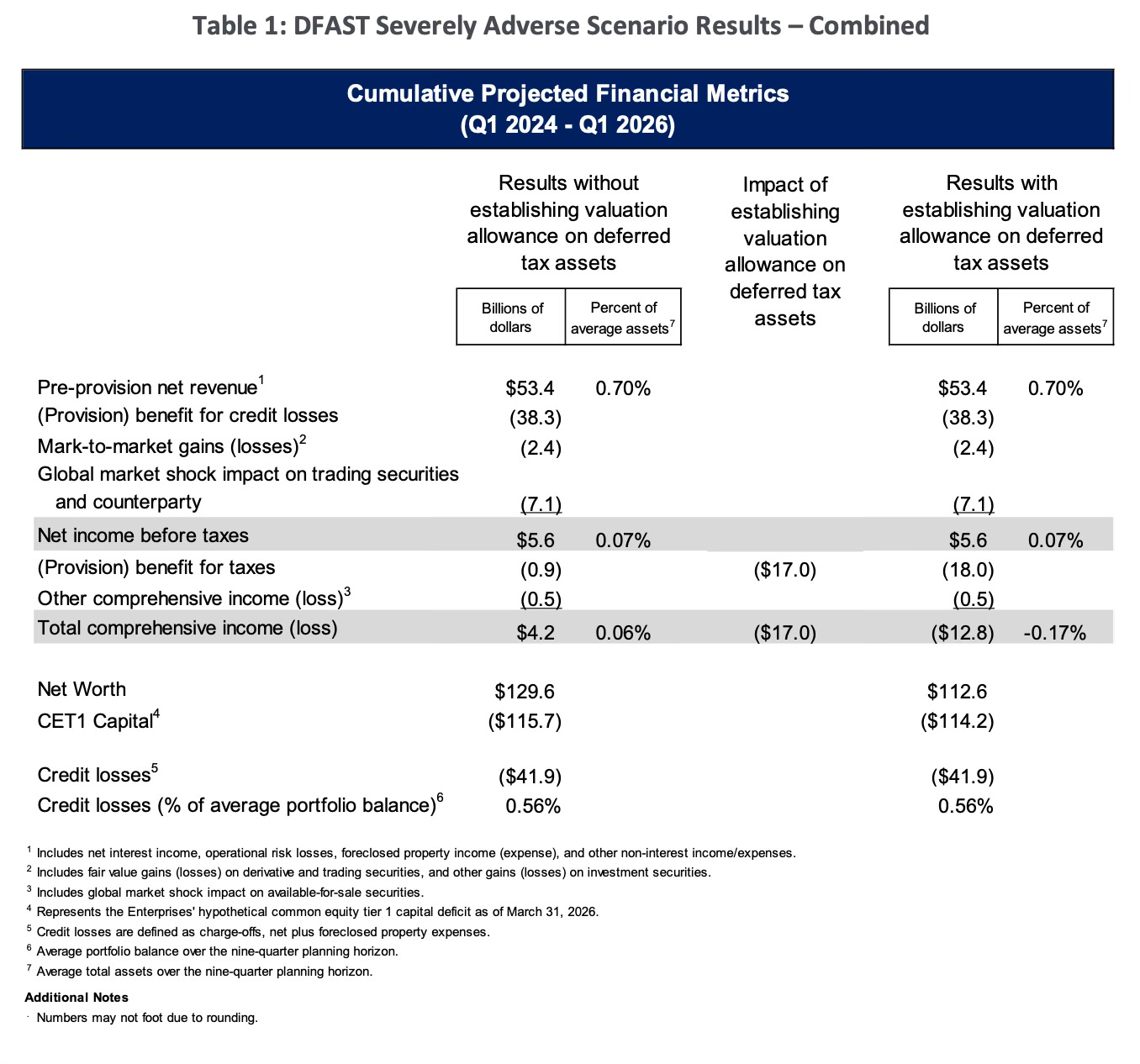

Every year since 2014, FHFA has conducted Dodd-Frank stress tests (DFAST) on Fannie and Freddie using the same “severely adverse” scenario the Fed applies to systemically important banks. The latest test assumes unemployment hitting 10%, home prices falling 33% from peak, commercial real estate down 30% and a global market shock that reprices mortgage-backed securities.

The results are public. Here’s what they show.

Under the severely adverse scenario, Fannie Mae ends the stress period with a CET1 capital deficit of -$77.9 billion. Freddie Mac ends with a deficit of -$37.8 billion. Combined: a -$115.7 billion hole.

That’s not a “fortress.” That’s insolvency.

And this is using the regulator’s own model, with today’s improved credit book, under a scenario that’s actually less severe than 2008 in some dimensions (home prices fell over 40% in the hardest-hit markets during the actual crisis).

The test also reveals why Ackman’s capital ratio looks better than it is. The GSEs report about ~$173 billion in “net worth”—retained earnings plus the original preferred stock. But CET1 capital under the regulatory framework is considerably lower. Deferred tax assets get haircut. Certain other adjustments apply. When you run the numbers correctly, the starting position is weaker and the stress losses are larger.

The 2.5% Standard That Isn’t

Even setting aside the stress test results, FHFA doesn’t treat 2.5% as adequate.

The 2020 Enterprise Regulatory Capital Framework describes 2.5% as a “backstop leverage requirement”—a floor, not a target. The framework pairs it with a 1.5% prescribed leverage buffer, implying something closer to 4% when fully phased in. Later revisions softened some requirements, but the principle holds. The people paid to design the rule didn’t think 2.5% was sufficient for a conservatorship exit.

Mark Calabria, the first Trump administration’s head of FHFA who actually championed GSE release, wanted higher capital than what Ackman is now celebrating. Calabria pushed for the Enterprise Regulatory Capital Framework precisely because he believed the GSEs needed far more capital before any exit could be contemplated. The irony is that the regulator most sympathetic to privatization set requirements that today’s capital still doesn’t meet.

So when Ackman calls 2.5% “fortress level,” he’s describing a capital ratio that falls short of the regulator’s own minimum for release, that produces a ~$116 billion hole under the regulator’s own stress test, and that he arrived at by comparing current capital to losses measured with years of hindsight rather than what Treasury actually had to inject in real time.

The Systemic Comparison

“Fortress” is a comparative word. So let’s compare.

When regulators assess whether a financial institution can survive a crisis, they focus on CET1—Common Equity Tier 1 capital. This is the strictest measure. Common stock plus retained earnings, minus deductions for assets that might not actually be there when you need them (like certain tax benefits). It’s the capital that absorbs losses first and that’s unambiguously available when markets seize.

The Fed requires systemically important banks to hold a 4.5% minimum CET1 ratio, plus a stress capital buffer of at least 2.5%, plus an additional G-SIB surcharge of at least 1.0%. That’s 8%+ before institution-specific add-ons. JPMorgan’s total requirement is 11.5%, Citi’s is 11.6%, Goldman’s is 10.9%.

Now, a fair objection. Comparing capital requirements for systemically important global banks and the GSEs isn’t totally apples to apples.

Bank CET1 requirements are measured against risk-weighted assets, not total assets. The GSE leverage backstop—the 2.5% floor Ackman cites—is measured against Adjusted Total Assets, much closer to the full balance sheet. Since risk-weighting reduces the denominator, a bank’s “8% of RWA” might translate to something like 4-6% of total assets depending on business mix. The gap narrows once you translate to common terms.

There’s also a complexity argument. Banks face more risk channels: deposit runs, diversified loan books, trading desks, derivatives, prime brokerage, operational risk across sprawling global operations. The GSEs are essentially monoline mortgage credit businesses. FHFA’s capital framework is mortgage-tailored and includes a 20% risk-weight floor to prevent capital requirements from drifting too low in benign times.

Fair enough. But the complexity argument cuts both ways.

A diversified bank can have its commercial real estate book blow up while its credit card portfolio stays healthy. JPMorgan can lose money in London while making money in New York. Risk gets spread across asset classes, geographies, and business lines.

The GSEs don’t have that luxury.

When housing breaks, their entire $7.7 trillion book breaks simultaneously. Every loan, every guarantee, every exposure—all correlated to the same underlying asset class. This is the difference between concentrated and diversified risk. Banks may be more complex, but the GSEs face a purer, more correlated exposure to a single systemic risk factor. American home prices.

That correlation is precisely what makes housing crises so devastating and precisely why the GSEs needed $191.5 billion when the last one hit.

There’s another problem with the apples-to-oranges defense. FHFA’s capital framework doesn’t just include the 2.5% leverage backstop. It also includes risk-based requirements—4.5% CET1, 6.0% Tier 1, and 8.0% adjusted total capital, all measured against risk-weighted assets—plus buffers that mirror the bank framework. When you add it all up, the combined requirement under ERCF comes to roughly $234 billion in CET1 for both enterprises. Today the GSEs hold only ~$173 billion.

So even on the GSEs’ own tailored, mortgage-specific framework—designed to be less demanding than what banks face—they’re $61 billion short. Before any stress scenario is applied.

Ackman is pointing to the regulatory floor and calling it a fortress. The regulator designed that floor as a backstop to the binding constraint—and the GSEs don’t even meet the binding constraint yet.

The Mortgage Insurance Fallacy

Ackman’s other supporting argument for 2.5% is that it matches what private mortgage insurers hold—and they’re guaranteeing the riskier first-loss portion of loans while the GSEs only guarantee the senior piece.

This comparison misunderstands how the system works and why it matters.

Private mortgage insurers cover the first-loss slice on high-LTV loans, typically where borrowers put down less than 20%. On a loan with 5% down, the PMI covers roughly the first 15-20% of losses, the GSE guarantee covers the senior remainder.

But not all GSE loans have private mortgage insurance. Loans with 20% or more down (a substantial share of the book) have no PMI protection at all. On those loans, the GSE takes credit risk from dollar one.

Even where PMI exists, coverage comes with limits, exclusions, and counterparty risk. When mortgage insurers got stressed in 2008, several failed or stopped writing new business entirely.

There’s also the question of scale. Total private mortgage insurance risk-in-force is on the order of a few hundred billion dollars. The GSEs guarantee roughly $8 trillion. Even if per-dollar risk is lower on the senior slice, aggregate exposure is an order of magnitude larger.

But the real issue is what happens when things break.

Mortgage insurers are private companies. They can fail—and they have failed. Several went under or into runoff in 2008-2009. When a mortgage insurer fails, its losses stop at its capital. The system absorbs it and moves on.

The GSEs cannot be allowed to fail. When their capital runs out, the taxpayer is next in line. That’s not speculation—it’s exactly what happened in 2008.

When Triad Guaranty Insurance Corp (a private mortgage insurer) was forced into liquidation in 2008, the mortgage market kept functioning. When Fannie and Freddie collapsed, Treasury had to write a $191.5 billion check as the system broke or the financial system would have seized. That’s the difference between a containable failure and a systemic one.

Comparing GSE capital to PMI capital is like comparing a regional airport to air traffic control. One can shut down and flights get rerouted. The other goes down and every flight gets grounded.

The Guarantee That Never Leaves

This is where Pershing Square’s actual proposal gets more sophisticated than the social media pitch. And where it falls apart most completely.

The entire GSE business model depends on an implicit government backstop.

The GSEs borrow at rates 20-40 basis points lower than comparably-rated private financial institutions, a funding advantage that exists solely because investors believe the government stands behind them. That spread, applied across trillions of dollars in debt, is enormously valuable. It’s why the business model works. It’s why the guarantee fees are profitable. It’s why private capital can’t compete.

Ackman’s pitch is circular. The GSEs have a “fortress balance sheet” that makes them safe to privatize. But the only reason the balance sheet works at all is because everyone knows the government backstop remains.

The Pershing Square presentation actually makes this tension explicit, probably without meaning to. They propose relisting the GSEs on the NYSE while keeping them in conservatorship, with the PSPAs (the Treasury backstop agreements) remaining in place. Their argument is that this gives Treasury a “mark to market” on its ownership stake without the risks of actual privatization.

But this creates its own problems.

While in conservatorship, the GSE boards “owe their fiduciary duties of care and loyalty solely to the conservator and not to either the company or our stockholders.”

That’s from Fannie Mae’s own 10-K—a disclosure the company is legally required to make to warn investors about exactly this risk.

So Ackman is asking investors to buy shares in companies whose boards have no legal obligation to act in shareholders’ interests, hoping the government eventually decides to exit conservatorship and let the business model work. It’s Schrödinger’s privatization—simultaneously public and private, government-backed and independent, until someone opens the box and forces a choice.

What happens when someone opens the box? Answer: either the government formally guarantees them, killing the “privatization” narrative, or it doesn’t, and funding costs spike.

The administration’s own statements reveal the incoherence:

“We’re committed to making sure that there is no change in the spread of mortgages over Treasuries.” -Treasury Secretary Bessent in August 2025

“What we want to do is keep the price of a home mortgage as low as mathematically possible.” - Commerce Secretary Lutnick in September 2025

“…I am working on TAKING THESE COMPANIES PUBLIC, but I want be clear, the U.S. Government will keep its implicit GUARANTEES…” - President Donald Trump in May 2025

These commitments are in tension with each other. If you keep mortgage spreads unchanged, you’re keeping the implicit guarantee. If you keep the implicit guarantee, you’re not actually privatizing the risk. If you’re not privatizing the risk, you’re not removing liabilities from the government’s balance sheet.

The administration wants to book a one-time gain, keep mortgage rates low, maintain the implicit guarantee and call it “privatization.”

The $300 Billion “Profit” That Isn’t

Ackman promises taxpayers a $300 billion windfall from this transaction—on top of the $301 billion already collected in dividends.

The presentation elaborates. Treasury earned an 11.6% IRR on its investment through dividends, roughly $25 billion more than what would have been owed under the original 10% preferred stock terms. Therefore the Senior Preferred Stock should be deemed “repaid,” Treasury should exercise its warrants for 79.9% of the common stock, everyone should celebrate.

Let’s unpack what this actually means.

The IRR calculation treats all dividends as returns on the original investment. But the net worth sweep wasn’t a negotiated coupon—it was implemented in August 2012, just as the companies returned to profitability, requiring 100% of GSE earnings to be swept to Treasury. At the time, the broad consensus was that the GSEs would eventually be wound down. The dividend wasn’t a return on risk-taking. It was a policy decision to prevent capital accumulation while policymakers figured out what to do next.

More importantly, the IRR on past cash flows doesn’t address the value of the ongoing guarantee Treasury is providing.

The GSEs borrow at rates only slightly above Treasury yields because investors believe the government stands behind them. Without that implicit backing, funding costs would rise, the business model would strain, and as 2008 demonstrated, the whole edifice could collapse under stress.

A $300 billion one-time payment doesn’t come close to compensating taxpayers for unlimited tail risk the next time the housing market breaks. Put differently, Treasury would be selling a permanent put option on $8 trillion in housing exposure for a one-time premium—and calling it profit. The $301 billion already collected in dividends wasn’t a windfall. It was repayment for the $191.5 billion bailout plus compensation for the risk Treasury absorbed during the crisis. Calling anything beyond that “profit” ignores that the backstop is still in place.

So the “$300 billion profit” isn’t really profit. It’s the present value of selling the upside while keeping the downside.

Heads, shareholders make a fortune. Tails, taxpayers eat the next crisis.

The Stock Move That Tells You Everything

The fact that FNMA and FMCC shares move wildly based upon administration statements and perceived market probabilities of privatization tells you exactly what’s being priced here.

It’s not fundamentals. The companies haven’t become more profitable. The capital hasn’t grown faster. The credit quality hasn’t improved.

What’s changed is the perceived probability that the government will transfer value from taxpayers to shareholders—either by deeming the senior preferred “repaid” without actually removing the backstop, or by letting the GSEs exit conservatorship without adequate capital, or by maintaining the implicit guarantee while allowing private investors to capture the spread.

Every one of those outcomes is a wealth transfer. The stock price reflects the expected value of that transfer, not any improvement in the underlying business.

What This Is Actually About

None of this is an argument against owning FNMA or FMCC common. Markets can stay irrational for years, politics can be lucrative and the U.S. government has a long tradition of turning temporary structures into permanent ones. Holders of the stock prior to Trump’s election have paid off massively (although both stocks are now down about 50% from the September highs on concerns the IPO may be delayed).

Nor is this an argument that the GSEs should remain in conservatorship forever. Seventeen years is an anomaly. The conservatorship was designed as a temporary measure and there are legitimate reasons to want resolution.

But it is an argument against believing the story that’s being told.

A fortress holds without reinforcement.

In 2008, reinforcement cost $191.5 billion on a $5 trillion book. Today the book is $7.7 trillion. The regulator’s own stress test shows a -$115.7 billion capital hole under adverse conditions. The “seven times realized losses” number only works if you measure losses with hindsight instead of capital needs in real time. The mortgage insurer comparison ignores that mortgage insurers can fail and the GSEs cannot. The “privatization” being proposed keeps the government backstop in place while transferring the upside to shareholders.

And the $300 billion ‘profit’ is just what you collect when you sell catastrophic insurance priced as if the catastrophe will never come.

The administration wants to monetize these assets and resolve a conservatorship that was never meant to last seventeen years. That’s a legitimate policy goal. But let’s be honest about what’s actually happening. The government is being asked to keep providing unlimited tail risk protection while giving up its claim on the profits.

That’s not a fortress. It’s a future taxpayer-funded bailout disguised as an IPO.

Share this with anyone who thinks a 2.5% capital ratio is "fortress level!

📨 Housing investors, policy makers and C-suite execs keep forwarding this. Stop getting it late — subscribe now!

Sources and Further Reading

Regulatory Stress Testing (DFAST)

FHFA: 2024 Dodd-Frank Act Stress Test Results – Severely Adverse Scenario (August 2025; shows combined CET1 deficit of -$115.7 billion under severely adverse conditions)

Enterprise Regulatory Capital Framework

FHFA: Enterprise Regulatory Capital Framework Final Rule (December 2020; establishes 2.5% leverage backstop + 1.5% prescribed leverage buffer)

Pershing Square Materials

Pershing Square: “Promises Made, Promises Kept” Presentation (November 2025; 27-page investor deck on GSE relisting proposal)

Bill Ackman on X (December 2025 thread on Fannie/Freddie investment thesis)

GSE Company Filings (Fiduciary Duty Disclosure, Capital, Senior Preferred)

Fannie Mae 2024 Annual Report (10-K) (includes conservatorship fiduciary duty disclosure)

Conservatorship Structure / Senior Preferred Stock Purchase Agreements

U.S. Treasury Press Release (January 14, 2021): Treasury and FHFA Amend PSPAs (allows GSEs to retain capital to “protect taxpayers”)

Administration Statements on GSE Privatization

Fox Business: Treasury Secretary Bessent on GSE Reform (August 27, 2025; “committed to making sure there is no change in the spread of mortgages over Treasuries”)

CNBC: Commerce Secretary Lutnick on Fannie/Freddie IPO (September 11, 2025; “mark to market” and “keep the price of a home mortgage as low as mathematically possible”)

Truth Social: President Trump on Fannie Mae & Freddie Mac (May 27, 2025; “the U.S. Government will keep its implicit GUARANTEES”)

Bank Capital Requirements (G-SIB Comparison)

Federal Reserve: Large Bank Capital Requirements (CET1 minimums, stress capital buffers, G-SIB surcharges)

Historical Treasury Support / Crisis-Era Data

Congressional Budget Office: Fannie Mae, Freddie Mac, and the Federal Role in the Secondary Mortgage Market(includes implicit guarantee valuation estimates)

Federal Reserve History: Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac in Conservatorship

Academic / Policy Research

Cato Institute Working Paper: Conservatorship, Creditors, and the Future of Fannie and Freddie (Krimminger & Calabria, 2015; argues SPS should be treated as repayment with interest per conservatorship precedent)

American Enterprise Institute: Housing Finance Policy Center (various GSE reform analyses)